As athletes, we dedicate lots of time to developing and training our muscles, depending on our goals. What if there is another part of the body to train is not a muscle at all, but instead an aspect of our nervous system?

What we do, say, and feel is largely dictated by our nervous system. The body is an intelligent organism, and it will do everything in its power to protect itself, especially if it feels like it’s under attack and unsafe. However, it can often protect itself from an attack that isn’t truly life threatening, such as traffic on the way to the gym, comparing yourself to others on social media, getting an email from the boss, etc.

To perform at our best and become resilient, the nervous system deserves attention and maintenance, especially during challenging and uncertain times. One of the foundations of peak mental health is a well-regulated nervous system.

“Many of the perceived threats we encounter these days are not physical but rather cognitive—there are plenty of things we worry about that do not require a physical escape or fight. However, our bodies have evolved to react to stress in a very physical way, leading to heightened sympathetic nervous system activity and many symptoms of anxiety,” explain Tchiki Davis, Ph.D., and Sarah Sperber.

If we are unable to get our nervous system at a baseline regulated state when there aren’t any real threats, all of the mindset-work we do might be at a standstill. More or less, even if you can rationalize that an anxiety inducing “threat” isn’t actually going to harm you, doesn’t necessarily mean you can get your nervous system’s response to anxiety back under control.

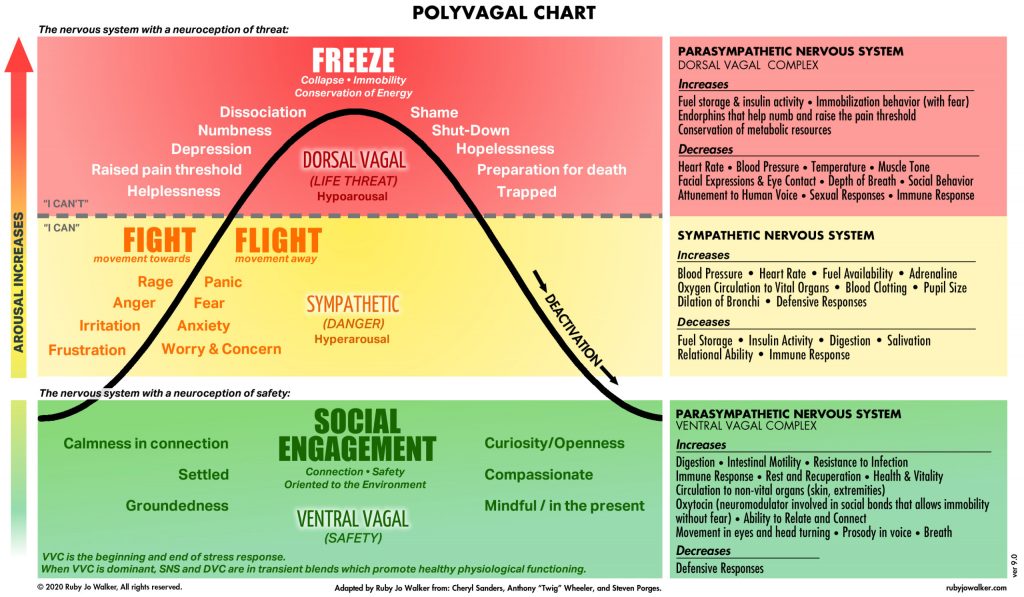

Let’s look at some of the functions of the nervous system:

- Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) – When heightened, this is often referred to as a “fight or flight” state, which produces energy for survival. We can respond with anger, rage, irritation, or frustration to fight off danger. In a flight response, we can experience anxiety, fear, or panic. Our physiological response is an increase in blood pressure, heart rate, and adrenaline, while decreasing digestion, pain threshold, and immunity responses.

- Second, the dorsal vagal or “freeze” state, which is our most primordial pattern, also known as the emergency state. This implies that we are entirely locked down, we may feel hopeless and that there is no way out. We are prone to feeling melancholy, conserving energy, dissociating, feeling overwhelmed, and feeling helpless in this state. Physiologically, we enhance our fuel stores and insulin activity, as well as our pain tolerances.

- Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS) – Also known as the ventral vagal state when dominant, which helps us to relax and slow down. We get a physiological boost in resistance to infection and other immune responses, circulation, digestion. It is also easier to feel connected to ourselves and the world.

There is a flow between these three states throughout the day in a healthy, regulated nervous system. In the presence of a real or perceived threat, the ventral vagal state shuts off and the survival mechanisms are switched on so we can protect ourselves. Once we have returned to safety, we can return to flowing between the three states. Since we can adapt to challenges, we don’t get stuck in any particular state.

Taking a deeper dive into this process, when we experience an incident that causes a fight, flight, or freeze response, AMPA receptors on the surface of the neuron flare up, encoding the experience. These are our troops who are standing at attention, alert to keep us secure. Stress hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline are released, which trigger protein production by instructing the amino acid glutamate to bind to the AMPA receptors and cement them in place. They will remain that way indefinitely until the memory is reconsolidated and the trauma is alleviated. Meanwhile, the hippocampus next door functions as a reporter, recording all the memories and observing all the sensory input from the environment (even things you aren’t consciously focused on). Because of this, anything remotely similar to the initial negative event will cause the AMPA receptors to catch on immediately and cue the body to release stress hormones.

Lifters often discuss how “central nervous system (CNS) fatigue” can occur during overreaching phases or when not fully recovered from training. A similar experience follows being chronically stressed if you ignore the signs of a dysregulated nervous system. However, the chain of events described above can be interrupted and eventually stopped through healthy habits that promote feel-good neurochemicals, such as serotonin, and reframing or neutralizing difficult memories through professional therapeutic guidance, memory reconsolidation, or hypnosis.

We can change our brains and patterns to be more resilient to stress!

Here are some practical tools that can help anyone learn natural stress relief and self-regulation skills to shift into well-being.

An important first step is to become aware of how your body manifests anxiety (fight or flight) or depression (freeze or faint), which will allow you to really tune into your body and understand how you feel in that state to help yourself get out of it. You’ll also want to identify triggers for these states, as well.

Explore Different Ways of Moving Your Body (stretching, yoga, dancing, etc.)

You probably have already noticed that a good workout can reduce anxiety. But if you’re already quite anxious, remember you’re also piling more stress onto an already stressed system. But there are other ways to get the positive effects without grabbing your lever belt. Shake it like a saltshaker. Literally. Shaking your body helps release tension and overabundance of adrenaline and allows you to focus on something other than feeling overwhelmed. There’re also more gentle practices like yoga; reviews suggest that it can help with anxiety and depression by reducing the impact of increased stress responses. In terms of yoga’s psychophysiological effects, new research suggests that it may affect PNS tone and reduce stress hormones. [i] – 3

Cold Water Exposure

Researchers have found that exposing yourself to cold temperatures regularly can lower the sympathetic (fight/flight) response and increase parasympathetic activity through the vagus nerve.4, 5 You can do this by placing an ice pack on your chest, splashing cold water on your face, or take a cold shower. As a side note, if you use this method regularly, you probably don’t want to do it immediately post-training, as consistently doing so can blunt hypertrophy.6

Reorient to the Present/Mindfulness

Identify five things you can see, four things you can touch, three things you can hear, two things you can smell, and one thing you can taste. This simple exercise can snap you out of past-focused depression or future-focused anxiety and bring you into the present.7

Practice Meditation

We all knew this was in the mix. This is one of the best techniques you can practice. Among the plethora of benefits it provides, it trains our minds to regularly activate the body’s natural relaxation response so that stress simply cannot take over, allowing us to maintain out mental/emotional well-being.8

Breathwork

Slow, deep breathing can be used to effectively manage emotions of worry (including PTSD symptoms) and stress, according to a growing number of studies. The hypothesis behind these findings is that we naturally breathe slowly and deeply when we are comfortable and peaceful. As a result, practicing slower breathing can help the autonomic nervous system (ANS) return to parasympathetic dominance, resulting in more balanced levels of arousal.9 – 11

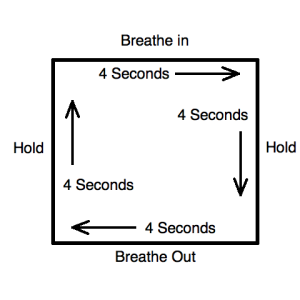

There are a few ways to approach breathwork and a great way to start is with a technique called box or square breathing, which is famously used by U.S. Navy SEALs.

Start by inhaling through the nose for a count of four, hold for a count of four, exhale through the mouth for a count of four, and hold the breath for a count of four. Be conscious of breathing deeply into your lower belly and feeling the air filling and leaving your lungs.

Other helpful tools:

Moderate your screen time 12

Connect with nature and sunshine 13

Ensure you are not deficient in vitamin B and D 14 – 17

Try EFT tapping (emotional freedom technique) 18, 19

Finally, don’t hesitate to seek professional help from someone who can not only teach you to use these techniques, but also help you to directly assess prior trauma, unhealthy patterns, troubling thoughts, anxiety, and more.

Somatic work is important in helping us regulate our nervous system, as well as becoming more familiar with our own feelings and needs. In doing so, we can step further into our true selves outside of childhood/cultural/societal conditioning. This is how we can begin to develop resilience and appropriately respond to life’s challenges.

If you’d like guidance in your journey, please reach out!

[i] Montero-Marín, J., Asún, S., Estrada-Marcén, N., Romero, R., & Asún, R. (2013). Effectiveness of a stretching program on anxiety levels of workers in a logistic platform: a randomized controlled study. Atencion primaria, 45(7), 376–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aprim.2013.03.002

2 Wipfli, B., Landers, D., Nagoshi, C., & Ringenbach. (2011). An examination of serotonin and psychological variables in the relationship between exercise and mental health. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 21(3), 474 – 481.

3 Kirkwood, G., Rampes, H., Tuffrey, V., Richardson, J., & Pilkington, K. (2005). Yoga for anxiety: a systematic review of the research evidence. British journal of sports medicine, 39(12), 884–891. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2005.018069

4 Muzik, O., Reilly, K. T., & Diwadkar, V. A. (2018). “Brain over body”-A study on the willful regulation of autonomic function during cold exposure. NeuroImage, 172, 632–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.01.067

5 Shevchuk N. A. (2008). Adapted cold shower as a potential treatment for depression. Medical hypotheses, 70(5), 995–1001. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2007.04.052

6 Fyfe, J. J., Broatch, J. R., Trewin, A. J., Hanson, E. D., Argus, C. K., Garnham, A. P., Halson, S. L., Polman, R. C., Bishop, D. J., & Petersen, A. C. (2019). Cold water immersion attenuates anabolic signaling and skeletal muscle fiber hypertrophy, but not strength gain, following whole-body resistance training. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985), 127(5), 1403–1418. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00127.2019

7 Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 78(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018555

8 Ospina, M. B., Bond, K., Karkhaneh, M., Tjosvold, L., Vandermeer, B., Liang, Y., Bialy, L., Hooton, N., Buscemi, N., Dryden, D. M., & Klassen, T. P. (2007). Meditation practices for health: state of the research. Evidence report/technology assessment, (155), 1–263.

9 Clark, M. E., & Hirschman, R. (1990). Effects of paced respiration on anxiety reduction in a clinical population. Biofeedback and self-regulation, 15(3), 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01011109

10 Pal, G. K., Velkumary, S., & Madanmohan (2004). Effect of short-term practice of breathing exercises on autonomic functions in normal human volunteers. The Indian journal of medical research, 120(2), 115–121.

11 Perciavalle, V., Blandini, M., Fecarotta, P., Buscemi, A., Di Corrado, D., Bertolo, L., Fichera, F. & Coco, M. (2017). The role of deep breathing on stress. Neurological Sciences, 38(3), 451-458.

12 Hancock, J. T., Liu, X., French, M., Luo, M., and Mieczkowski, H. (2019). “Social media Use and Psychological Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis,” in International Communication Association Conference, Washington, DC.

13 Gladwell, V. F., Brown, D. K., Barton, J. L., Tarvainen, M. P., Kuoppa, P., Pretty, J., Suddaby, J. M., & Sandercock, G. R. (2012). The effects of views of nature on autonomic control. European journal of applied physiology, 112(9), 3379–3386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-012-2318-8

14 Young, L. M., Pipingas, A., White, D. J., Gauci, S., & Scholey, A. (2019). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of B Vitamin Supplementation on Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety, and Stress: Effects on Healthy and ‘At-Risk’ Individuals. Nutrients, 11(9), 2232. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092232

15 Penckofer, S., Kouba, J., Byrn, M., & Estwing Ferrans, C. (2010). Vitamin D and depression: where is all the sunshine? Issues in mental health nursing, 31(6), 385–393. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840903437657

16 Wrzosek, M., Łukaszkiewicz, J., Wrzosek, M., Jakubczyk, A., Matsumoto, H., Piątkiewicz, P., Radziwoń-Zaleska, M., Wojnar, M., & Nowicka, G. (2013). Vitamin D and the central nervous system. Pharmacological reports : PR, 65(2), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1734-1140(13)71003-x

17 Young, L. M., Pipingas, A., White, D. J., Gauci, S., & Scholey, A. (2019). A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of B Vitamin Supplementation on Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety, and Stress: Effects on Healthy and ‘At-Risk’ Individuals. Nutrients, 11(9), 2232. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092232

18 Clond, M., (2016). Emotional Freedom Techniques for Anxiety: A Systematic Review With Meta-analysis. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 204(5), 388-395. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000483

19 Nelms, J. & Castel, D. (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized trials of Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) for the treatment of depression. Explore: The Journal of Science and Healing, 13(6), 416-426. doi:10.1016/j.explore.2016.08.001

I struggle with meditation. This is very informative.