Whether you have been training for decades, or are just getting started, there have been/will be times where you lack the time to train the way you would otherwise like to.

Personally, I have grown pretty accustomed to needing some time saving strategies especially as I’ve started to get older. Gone are the days of unlimited gym time, and in fact, some weeks it can feel a bit like putting together a puzzle. Fortunately, there are a number of tools at our disposal to navigate those situations and keep the train moving in the right direction. At worst, we can usually at least hold our ground until we can pick back up with normally scheduled programming.

Exercise selection and execution

Perhaps the first step one should take when trying to make the most efficient use of their time is by looking at their exercise selection and execution. In fact, I believe this should generally be the first thing you examine prior to making any significant changes to any of your/your client’s acute training variables.

Are there better tools available for the goal at hand?

Optimal exercise selection is a hot topic right now but this isn’t a post to discuss that at length. However, if there are clearly more efficient exercises for a given goal, refining that alone could save a considerable amount of time by increasing the stimulus within each set and/or the amount of time available.

Is there room to refine the technical execution of the programmed movements?

As a coach, I have encountered a number of circumstances where we have gotten more out of a given amount of volume (or even made better progress with less) simply by refining execution to more efficiently train the muscle group in question. Sloppy sets still take time, and the goal is to make efficient use of our time.

Are compound movements being prioritized within the program?

Most people would agree that if forced to pick only a handful of exercises to perform, most would be multi joint/compound movements due to their ability to train multiple muscle groups at a time. If you are in a pinch and need to cut a session short, it’s probably better to skip isolation work vs a compound movement.

Are there machines available to perform the task at hand?

While there are many machines which can provide a stimulus in a manner unachievable with free weights, they are popular in commercial gyms primarily due to their convenience. Some machines are certainly better than others, but including quality machine work within your program can certainly save you some time by not having to walk back and forth with weights to get set up. Obviously there are plenty of situations where free weights are heavily prioritized (e.g., powerlifting), so machine work has less utility in such cases.

Achieving the desired stimulus in less time

As we progress through our training careers, many of us are faced with a cruel dilemma. We need to increase the training stimulus over time, which often coincides with having less time as a whole or acutely, to achieve it.

Fortunately, there are a handful of useful tools at our disposal which save time/increase the density of our training, while usually getting as much (or perhaps sometimes more) out of the time available.

Supersets

A superset is when you alternate between two different exercises, sometimes with or without some brief rest in between them.

Antagonist Paired Sets involve supersetting/alternating between movements that train opposing/antagonistic muscle groups, with brief/no rest between them (e.g., chest/back, quads/hamstrings).

Research has shown that antagonistic paired sets can not only save considerable time (Paz et al., 2017), but can even enhance performance (total volume) for both upper (Paz et al., 2017), and lower body exercises (Maia et al., 2014) when compared to traditional set(s).

Given the opposing role of the antagonistic muscle group(s) during a movement, it’s suggested that the carryover fatigue and reciprocal inhibition of the antagonistic muscle groups during agonist work could increase agonist activation when performing it (Carregaro et al., 2011).

Of notable importance, it also appears possible to rest too long between exercises to reap the performance enhancing benefits when using antagonistic paired sets. The study from Maia et al. (referenced above) examined the potential benefits on leg extension performance when performing leg curls immediately prior to leg extensions vs just doing the leg extensions alone. There was a significant increase in reps performed (vs just doing leg extensions) when there was minimal rest, 30s, or 1 min rest between movements. However, resting 3 or 5 min after the leg curls before performing the leg extensions did not show a significant performance benefit over the group just doing leg extensions (Maia et al., 2014). The Paz, et al. study referenced above had no rest between movements (but did rest 2 min between sets), and still found performance benefits for both exercises (bench/row). However, in other research comparing antagonistic paired sets with rest intervals of 1 min, 2 min, 3 min, or self selected (averaged out to 2.5 min) for both bench/row & overhead press/pulldown, the least amount of volume was performed in the 1 min group, while the self selected and 3 min groups performed the most (Behenck et al., 2022). So, while it’s hard to give a narrow recommendation for rest, staying below 3 min of rest between antagonistic movements is probably a good idea.

I actually lean pretty heavily on these in my own training. I can’t honestly say I’ve noticed a robust performance benefit, but I also haven’t seen an obvious hit to performance either. That in conjunction with the time saved makes them a staple in my training, especially when time constrained.

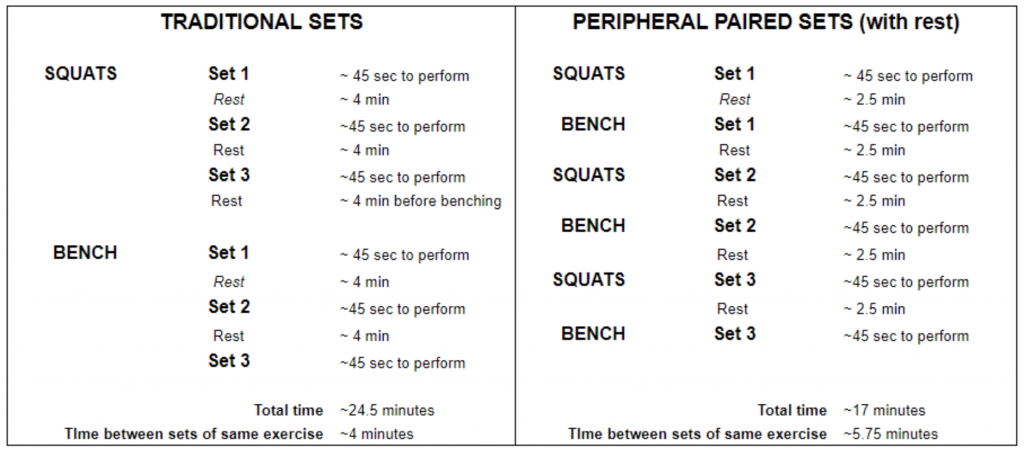

Peripheral Paired Sets involve supersetting/alternating between movements that train peripheral/“unrelated” muscle groups (e.g., chest/quads, biceps/calves).

The research on peripheral paired sets is pretty limited. A recent study compared traditional sets for smith machine squats and bench press vs. supersetting the two exercises. While more time efficient, the supersets resulted in less reps performed at higher velocities and less total volume (Peña García-Orea et al., 2022). However, it is worth noting there was no rest between the exercises (sounds awful), but only after both were completed before doing the next superset.

I use peripheral paired sets probably as much as I do antagonistic paired sets, but I would recommend still resting between sets of each exercise, especially when using heavy compound movements. When training at home, I often alternate sets of squats and bench since I have two racks. However, doing this in a commercial gym may not be feasible depending on the amount of racks and availability. Anecdotally, I actually feel it can sometimes improve my performance. This is very likely because it can be structured in a manner to reduce overall training time, while also increasing the time between sets of the same exercise. I suspect that could be offsetting any residual “global” fatigue which could potentially affect performance within the same movement. Example:

Grouped/Compound Sets involve supersetting movements that train the same muscle groups (i.e., leg extension/squat, bench press/flys) with no rest. In practice, these are generally performed in an effort to “pre-exhaust” a muscle group/region with the intent to increase muscle activation within the next movement. However, it’s important to point out that while EMG activity has at times been shown to be higher for some muscles with grouped vs separated supersets (Brentano et al., 2017), EMG amplitude is moreso a measure of excitation vs. muscle activation directly, and should not be considered a validated tool to predict hypertrophy and strength adaptations (Vigotsky et al., 2018, Vigotsky et al., 2022) .

From a performance standpoint, research has shown grouped supersets result in lower performance, compared to antagonistic paired sets or peripheral super sets (Weakley et al., 2020). While grouped supersets (bench w/ flys & leg press w/ leg ext) can result in higher EMG activity in some supporting muscle groups, it can come at the cost of higher muscle damage when compared to separated supersets (bench press w/ leg ext & leg press w/ flys) (Brentano et al., 2017).

Conceptually, grouped/compound supersets are actually quite similar in principle to extended set methods like rest pause and drop sets (both discussed in next section), in that they all involve minimal to short rest intervals.

I included grouped super sets here given they are a type of superset, and do save time. However, I rarely use these as a time saving strategy, for the reasons mentioned above.

Extended Set Methods

As the name implies extended set methods extend the work performed in an otherwise “traditional” set, and aim to achieve as much stimulus/more stimulus as a traditional multiple set model, but in less time. The commonly held rationale is to use peripheral fatigue to one’s advantage, in an effort to continue to accrue volume under high levels of motor unit recruitment.

Rest Pause Sets involve performing a set (generally close to failure), taking a short rest (~15-30s), and performing additional set(s), each with a short rest between them. This may be performed up until a total target number of reps is reached, or for a target number of smaller sets.

In terms of potential strength benefits compared to traditional sets, the research seems equivocal. There is volume equated research which shows no additional benefit of rest pause training on strength outcomes (Prestes et al., 2019), while others show a benefit (squat 1RM) (Enes et al., 2021).

When it comes to potential hypertrophy benefits of rest pause compared to traditional sets, the results are also a bit mixed. There is volume equated research which shows no significant benefit on hypertrophy (Enes et al., 2021), and volume equated research that shows an advantage for quad hypertrophy specifically, although the lack of progression structure in the traditional group may have influenced results there (Prestes et al., 2019).

Despite there not being a clear cut advantage for hypertrophy or strength when using rest pause compared to traditional sets, there appear to be few downsides in the short term, and they do save time.

Drop Sets involve performing reps until failure/close to failure, reducing the load (generally by ~20-30%), and immediately performing more reps until/close to failure, for one or more sets/drops with no rest (with additional drops in load in between).

Like rest pause, when it comes to the research comparing drop sets to traditional sets, there isn’t a convincing weight of evidence they provide additional benefits for strength and hypertrophy.

Some of the research showing a hypertrophy advantage for rest pause had the rest pause group performing more volume (Goto et al., 2004); however, there is also research where the rest pause groups performed more volume compared to the traditional, but experienced no additional increases in fat free mass (Fisher et al., 2016).

In volume matched research, there is research demonstrating no significant hypertrophy benefit of drop sets compared to traditional sets for both lower (Angleri et al., 2017, Enes et al., 2021) and upper body (Fink et al., 2018, Ozaki et al., 2018) movements.

Of importance, volume matching is often done through equating volume load or repetitions. When it comes to “hard sets”, many wonder how to “equate” for the stimulus achieved through traditional sets, since each drop includes a reduction in load. A well recovered set performed for a given number of reps will provide a greater stimulus/mechanical tension than performing that same number of reps with less load due to fatigue. Therefore it would make sense that drop set approaches may need more “sets”/drops to account for that. In support, in a couple studies comparing hypertrophy outcomes to 3 “traditional” sets, hypertrophy was similar when using 3 (Fink et al., 2018) to 4 (Ozaki et al., 2018) drop sets following the initial set. In other words, 3 traditional sets seems roughly equivalent to 1 set + 3-4 drops for hypertrophy.

Based on what we know, it seems clear the biggest advantage of drop set training is the time it can save. Compared to traditional sets, drop sets may reduce training time by more than half, both in volume matched (Fink et al., 2018), and non volume matched conditions (Ozaki et al., 2018).

Considerations for implementing extended set methods

For the sake of safety, it’s generally recommended that rest pause and drop set methods be reserved for machine and/or isolation work given you are training near failure across a number of sets.

Additionally, due to the fact isolation movements generally train less muscle overall, they generate less cardiovascular fatigue and mitigate the possibility for central fatigue mechanisms limiting the overall stimulus. While the overall pattern of data tends to show neutral to negative impacts on hypertrophy when using short rests with compound movements, short rests generally seem to have neutral to positive impacts when performing isolation work, likely for this reason. To read more about this topic in particular, Eric Helms wrote a great 3DMJ blog post about how we may be able to reconcile studies where rest-pause and drop sets produce similar hypertrophy as straight sets, despite some data showing short rest periods produce less hypertrophy than longer rest intervals.

Pliable training splits

Have you ever had your training schedule go awry and just think “Whatever, I’ll just start fresh on Monday?” Many of us like to view our training plan as having these crisp parameters that consistently fall within our normal weekly/daily routine. When that routine is forced to change, that can make us uncomfortable.

First, I think it’s a worthwhile reminder that our physiology doesn’t know what training split we are on. It’s easy to have the tendency to get halfway through a block, hit some unexpected scheduling issues, and then be tempted to scrap the block and start over. I know I’ve had to fight off this temptation before, but it’s completely unnecessary. Bailing on a split to “start again Monday” is like saying the same thing when going slightly over our caloric budget. We don’t have to be perfect to continue moving forward towards our goals.

When setting up a split, we need to first ask ourselves if it integrates flexibly with our schedule. Depending on the person, some splits are better than others from a time management perspective, especially when balancing the number of training days with the time commitment of each session.

For volatile schedules, one of the goals is to minimize excessive lag between training the same muscle groups should a microcycle need to be extended (even if it’s with a relatively small amount of volume). As a simple example, a once a week bodypart split that has your week interrupted and microcycle extended is going to result in a 7+ day lag between training the same muscle group. Simply increasing the frequency of a muscle group to 2-3 days/micro will prevent muscle group frequency disruptions (and may lead to better progress).

Maintaining is OK sometimes!

If deviating from what you consider optimal makes you uncomfortable, instead ask yourself “What does success look like in this specific situation?”, knowing what may be “optimal” for progress may be off the table at that point in time.

From a perspective of overall progress alone, doing less and holding ground is a substantially better option than skipping training entirely. That tendency to push things off until life calms down isn’t always unwarranted, but ask yourself if you are doing so to appease your preference for clean organization.

It should be encouraging to know it takes very little stimulus to maintain the majority of your muscle and strength. One study found that after 32 weeks, strength and hypertrophy was maintained with as little as ~ 33% (even less in younger individuals) of previous volume (Bickel et al., 2011). Those that can take what’s there will progress more in the long run than those with an “optimal or bust” attitude towards their training.

We are all eventually faced with situations where we need to find ways to train with limited time. Any successful training career requires pliability, and there is a lot we can do to make the best of these stretches.

References

Angleri, V., Ugrinowitsch, C., & Libardi, C. A. (2017). Crescent pyramid and drop-set systems do not promote greater strength gains, muscle hypertrophy, and changes on muscle architecture compared with traditional resistance training in well-trained men. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 117(2), 359–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-016-3529-1

Bickel, C. S., Cross, J. M., & Bamman, M. M. (2011). Exercise dosing to retain resistance training adaptations in young and older adults. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 43(7), 1177–1187. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e318207c15d

Behenck, C., Sant’Ana, H., Pinto de Castro, J. B., Willardson, J. M., & Miranda, H. (2022). The Effect of Different Rest Intervals Between Agonist-Antagonist Paired Sets on Training Performance and Efficiency. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 36(3), 781–786. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000003648

Brentano, M. A., Umpierre, D., Santos, L. P., Lopes, A. L., Radaelli, R., Pinto, R. S., & Kruel, L. F. M. (2017). Muscle Damage and Muscle Activity Induced by Strength Training Super-Sets in Physically Active Men. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(7), 1847–1858. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001511

Carregaro, R. L., Gentil, P., Brown, L. E., Pinto, R. S., & Bottaro, M. (2011). Effects of antagonist pre-load on knee extensor isokinetic muscle performance. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(3), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2010.529455

Enes, A., Alves, R. C., Schoenfeld, B. J., Oneda, G., Perin, S. C., Trindade, T. B., Prestes, J., & Souza-Junior, T. P. (2021). Rest-pause and drop-set training elicit similar strength and hypertrophy adaptations compared with traditional sets in resistance-trained males. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism = Physiologie Appliquee, Nutrition Et Metabolisme, 46(11), 1417–1424. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2021-0278

Fink, J., Schoenfeld, B. J., Kikuchi, N., & Nakazato, K. (2018). Effects of drop set resistance training on acute stress indicators and long-term muscle hypertrophy and strength. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness, 58(5), 597–605. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0022-4707.17.06838-4

Fisher, J. P., Carlson, L., & Steele, J. (2016). The Effects of Breakdown Set Resistance Training on Muscular Performance and Body Composition in Young Men and Women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(5), 1425–1432. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001222

Goto, K., Nagasawa, M., Yanagisawa, O., Kizuka, T., Ishii, N., & Takamatsu, K. (2004). Muscular adaptations to combinations of high- and low-intensity resistance exercises. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 18(4), 730–737. https://doi.org/10.1519/R-13603.1

Maia, M. F., Willardson, J. M., Paz, G. A., & Miranda, H. (2014). Effects of different rest intervals between antagonist paired sets on repetition performance and muscle activation. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 28(9), 2529–2535. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000000451

Ozaki, H., Kubota, A., Natsume, T., Loenneke, J. P., Abe, T., Machida, S., & Naito, H. (2018). Effects of drop sets with resistance training on increases in muscle CSA, strength, and endurance: A pilot study. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(6), 691–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2017.1331042

Paz, G. A., Robbins, D. W., de Oliveira, C. G., Bottaro, M., & Miranda, H. (2017). Volume Load and Neuromuscular Fatigue During an Acute Bout of Agonist-Antagonist Paired-Set vs. Traditional-Set Training. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 31(10), 2777–2784. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001059

Peña García-Orea, G., Rodríguez-Rosell, D., Segarra-Carrillo, D., Da Silva-Grigoletto, M. E., & Belando-Pedreño, N. (2022). Acute Effect of Upper-Lower Body Super-Set vs. Traditional-Set Configurations on Bar Execution Velocity and Volume. Sports, 10(7), 110. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports10070110

Prestes, J., A Tibana, R., de Araujo Sousa, E., da Cunha Nascimento, D., de Oliveira Rocha, P., F Camarço, N., Frade de Sousa, N. M., & Willardson, J. M. (2019). Strength and Muscular Adaptations After 6 Weeks of Rest-Pause vs. Traditional Multiple-Sets Resistance Training in Trained Subjects. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 33 Suppl 1, S113–S121. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001923

Vigotsky, A. D., Halperin, I., Lehman, G. J., Trajano, G. S., & Vieira, T. M. (2018). Interpreting Signal Amplitudes in Surface Electromyography Studies in Sport and Rehabilitation Sciences. Frontiers in Physiology, 8, 985. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2017.00985

Vigotsky, A. D., Halperin, I., Trajano, G. S., & Vieira, T. M. (2022). Longing for a Longitudinal Proxy: Acutely Measured Surface EMG Amplitude is not a Validated Predictor of Muscle Hypertrophy. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 52(2), 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01619-2

Weakley, J. J. S., Till, K., Read, D. B., Phibbs, P. J., Roe, G., Darrall-Jones, J., & Jones, B. L. (2020). The Effects of Superset Configuration on Kinetic, Kinematic, and Perceived Exertion in the Barbell Bench Press. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 34(1), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000002179

Leave a Reply