By: Jordan Galida

As powerlifters, we know the importance of training the squat, bench, and deadlift often. We know that in order to get better at them in competition, we must focus on performing them as efficiently as possible. When we are getting ready for a meet, we get more focused and train them heavier and harder. But what do we do after a meet (off season), or when we aren’t getting ready for a meet? We know we have to keep training the powerlifts, but we don’t need to go as heavy as if we were in meet prep. We know we need to accumulate some volume, so we just increase the reps on the powerlifts. Best of both worlds, right? Well, there is a better way. Instead of creating a Frankenstein hybrid approach, let’s let the powerlifts handle the skill adaptations and let other, more joint friendly, movements accumulate volume for us. With this strategy, we can effectively increase how competitive we are in a given weight class all while creating a less injurious training environment.

Weight Classes

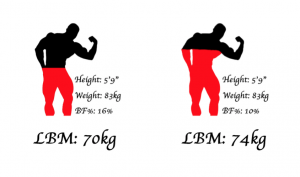

In powerlifting, the constraints are in the form of weight classes. However, weight classes are just that, only weight; they are independent of body composition. Two people can be in the same weight class with an enormous difference in body composition. Let’s say we have two identical lifters with the same height and weight in a given weight class; let’s say they are both 5’9” and compete in the 83kg weight class. One lifter is 10% body fat while the other is 16% body fat. One has an LBM of 74kg while the other has a LBM of 70kg. That’s an extra 4kg (9lbs) of muscle! That’s a HUGE advantage by the leaner competitor with more muscle. This is a contrived example, but it gets the point across.

Therefore, within-individual, the more muscle we can carry at a given weight class the more competitive we will be [1]. In fact, we know this to be the case in many sports, not just powerlifting [2, 3, 4, 5]. In order to be more competitive, we must create a more favorable body composition by:

- Reducing our body fat

- Increasing our lean body mass

Lowering body fat can be accomplished as a result of dropping a weight class or maintaining a weight class and increasing the amount of muscle at that given class. How do we accomplish this? We train in a way that allows us to accumulate enough volume for growth while still allowing for heavy specific training of the powerlifts, all while maintaining healthy connective tissues. I know what you are thinking, “but how much does muscle actually affect our strength abilities?”. Well, what is strength?

What is Strength?

As powerlifters, we are primarily concerned with strength. Mainly, strength in the powerlifts. Strength is the sum of two broad factors: 1) morphological – changes to the actual structure of the tissues, which includes both contractile and non-contractile tissues in and outside the muscle (like the titin molecule, intra-muscular connective tissue to enhance lateral force transmission, and also the tendon), increases in packing density of myofibrils, and hypertrophy (increases in muscle mass, and subsequent cross sectional area) and 2) neurological – increases in rate coding, motor skill improvement, decreases in inhibition, increases in voluntary activation, enhanced intra- and intermuscular coordination, enhanced rate of force production and improvements in self-efficacy and belief [6]. In layman’s terms, if we boil it down to what we can primarily improve through training:

Strength = Size + Skill

Skill development mainly stems from performing the movement you want to get better at, which in turn develops that specific skill (specificity) [7]. In terms of the powerlifts, that obviously means practicing the squat, bench, and deadlift. However, there is a caveat. You must not only be specific movement wise, but also intensity (load) wise. That is, you must practice the powerlifts with heavier weights as those are the kinds of loads you will be performing at a powerlifting meet. How heavy?

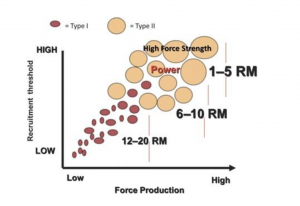

Henneman’s size principle states that larger motor units are recruited when larger amounts of force are required [8]. Thus, at around 85% of 1RM full motor unit recruitment occurs from the very first set of a rep, but they can still be increased further by being recruited more rapidly in succession to produce more force (rate coding). So, training intensity directly correlates with strength development [9]. The heavier the weights, the greater the strength development. With that understanding, if strength in the powerlifts is the main goal, then they should be trained at very high intensities to elicit the neurological adaptations necessary for strength development.

Connective Tissues

If training intensity is the governing factor of strength, then why not just program all of our training into maximal loading in order to reap the benefits? Because our connective tissue health will be severely impacted. Yes, those things holding our bodies together are also put under strain when lifting, it’s not just our muscles. The truth is, our muscles can take a beating, but our connective tissues can’t.

Our joints actually can get stronger, but it’s a slower process than that of our muscles and requires intensities of about 70% or above [10, 11]. Fortunately, our powerlifting provides more than enough stimulus for our connective tissues to get stronger, but we cannot push it any further as we are already at a maximum of joint stress. However, we do not want to completely remove the joint stress, as the heavy loads strengthen our joints. If we were to only use light loads, we could accumulate enough volume, but our connective tissues would fall behind in strength [12]. This would put us in an equally disadvantageous position as our muscles would be stronger than our joints which would make us more injury prone as well.

Our predicament is one of our connective tissues limiting us from accumulating sufficient volume from the heavy powerlifts. The solution? We utilize low intensity, joint friendly movements in order to accumulate the amount of volume required for hypertrophy. How do we do this?

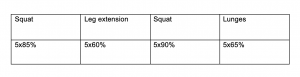

In this example, we have a hypothetical requirement of twenty sets per week in order for our quads to grow. Now, we know that all our time spent squatting should be spent at ~ 85% intensity range as our primary goal is strength adaptations. The remaining volume of ten sets can be distributed amongst accessory exercises that also train the quads like leg extensions and lunges. These exercises should be trained with intensities below 70% in order to give our connective tissues a break. Not only are these additional lifts easier on your joints, they allow you to distribute the stress amongst different muscle fibers thus more potential for different regional growth.

Your creativity is your limit with this principle. Finding ways to accumulate enough volume in a joint friendly, time efficient manner is up to your discretion as long as you don’t overload the tendons. Some other ways that I personally like to accomplish this is KAATSU (blood flow restriction training), difficult body weight variations like pistol squats, and eccentrics.

In conclusion, if you want to get stronger at a specific lift then you should train it at higher intensities. The powerlifts lend themselves perfectly to higher intensities, and somewhat poorly to lower intensities. Instead of simply increasing the reps on the powerlifts, keep them heavy and save your connective tissues all while stimulating more growth. Accumulating enough volume to grow is essential to be a competitive athlete in your weight class.

To learn more about the author, visit his website at jordangalida.com

References

- The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 2015 May;55(5):478-87. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.minervamedica.it/en/journals/sports-med-physical-fitness/article.php?cod=R40Y2015N05A0478

- Body Composition and Muscle Strength Predictors of Jumping… : The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Fulltext/2014/10000/Body_Composition_and_Muscle_Strength_Predictors_of.2.aspx

- (n.d.). School of Applied Health and Educational Psychology, Harrison Health and Human Performance Laboratory, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, Oklahoma, USA. bert.jacobson@okstate.edu. Retrieved from http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22290523/reload=0;jsessionid=vXxiZP3X2aizBSQ3je2b.12

- Relative Contributions of Strength, Anthropometric, and… : The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/nsca-jscr/Fulltext/2015/06000/Relative_Contributions_of_Strength,.2.asp

- Weyand, P. G., & Davis, J. A. (2005, July 15). Running performance has a structural basis. Retrieved from http://jeb.biologists.org/content/208/14/2625.short

- Folland, J. P., & Williams, A. G. (n.d.). The adaptations to strength training : Morphological and neurological contributions to increased strength. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1724110

- Winter, E., Abt, G., Brookes, F., Challis, J., Fowler, N., Knudson, D., Knuttgen, H., Kraemer, W., Lane, A., Mechelen, W., Morton, R., Newton, R., Williams, C. and Yeadon, M. (2018). Misuse of “Power” and Other Mechanical Terms in Sport and Exercise Science Research.

- Underlying Mechanisms and Physiology of Muscular Power : Strength & Conditioning Journal. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://journals.lww.com/nsca-scj/fulltext/2012/12000/Underlying_Mechanisms_and_Physiology_of_Muscular.3.aspx

- Schoenfeld, B. J., Wilson, J. M., Lowery, R. P., & Krieger, J. W. (n.d.). Muscular adaptations in low- versus high-load resistance training: A meta-analysis. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25530577

- Wiesinger, H. P., Kösters, A., Müller, E., & Seynnes, O. R. (2015, September). Effects of Increased Loading on In Vivo Tendon Properties: A Systematic Review. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25563908

- Bohm, S., Mersmann, F. and Arampatzis, A. (2018). Human tendon adaptation in response to mechanical loading: a systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise intervention studies on healthy adults.

- Mersmann, F., Bohm, S., & Arampatzis, A. (2017, December 01). Imbalances in the Development of Muscle and Tendon as Risk Factor for Tendinopathies in Youth Athletes: A Review of Current Evidence and Concepts of Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29249987

Awesome article!

What do you think about the concept that specific strength adaptations might decrease when low rep/high intensity work and high rep/low intensity work is mixed within relatively low time frames? I have heard some arguments for block periodized training approaches stating that mixing such heavy 85%+ work with low sub 70% intensity work within a single workout or even within a single training week would give you subpar results due to the 2 different kinds of stimuli interfering with each other.

Any thoughts on this?

Cheers!

Fabian,

Sorry for the extremely late reply, I read this comment a while ago and in my head a responded, but I must have forgotten to “post comment”. Good lord Jordan.

Trying to achieve two different adaptations at a single time will always be inferior than prioritizing one goal and ensuring training is specific to that. However, we tend to only see this interference effect when we reach very far into either end of the spectrum – think long distance endurance training and heavy, maximal strength training at the same time.

With the “hypertrophy range” we tend to stay within 4-30 reps. But mostly we only go above 15 reps if there is a specific need to use lighter intensities because of an injury or something like that. In theory, we could stay at the very bottom of the range and get the benefit of strength and hypertrophy at the same time. However this tends not to work out in practice. The problem is precisely what I’ve written about – we have to battle the strain on our connective tissues. The higher rep work is simply to provide the adequate volume while causing as little stress to the joints as possible.

So to answer your question, the interference effect of using the two ends of the hypertrophy range seem to have minimal affect on one another as long as you aren’t over training. With this method, we can accumulate the necessary volume for hypertrophy, and include high intensity work in doses that

1. Will not cause degradation of connective tissues

2. Allows some additional neurological adaptations to continue to induce strength gains which will further lead to increases in volume

Block periodization is great for an athlete with scheduled competitions that require peaking of performance, but for hypertrophy in general, it seems a little overkill for lack of a better term. We are simply trying to provide progressive overload in the proper dose, and safest manner possible. Our exercise selection for muscle growth is very broad, thus we are not restricted to complex periodization schemes to continue to progress as we will simply swap exercises once a certain movement requires complexity above things like daily undulating periodization.