“We’re going to try and see how little we can deadlift and not digress.” – Eric Helms.

The end of last year we had to make a big change in training with regard to my competition deadlift (Sumo). This was the only lift in my entire arsenal that was causing me great pain in my right posterior rib / intercostal area. We had already reduced volume down to an all-time low, but even the once per week, 3 to 6 reps was causing me issues that sometimes carried over into my other training movements. We had to abandon doing the sumo deadlift all together.

We wanted to try and find a suitable replacement that would have the most amount of carry over to my competition deadlift. We did a very short stent of suspended Zercher squats with a harness, essentially starting the squat from pins in the lowest position. This worked, but quite by accident we discovered a replacement that was even more similar. I could do a snatch grip deadlift without any pain to my troubled area and over the course of the next 4 months, we incorporated those into the program at 1x per week frequency using fixed reps of 3 x 3 all the while increasing the load every 2 weeks. When it came time to perform on the platform, the result of the approach was outstanding.

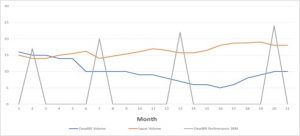

Louis Simmons “West Side Barbell” book of methods advocates a similar approach. Essentially, it suggests doing a different variation of a competition lift every 2 to 4 weeks. While we don’t totally buy into this approach, it would appear under certain contexts the approach does have merit (the specific context will make more sense later in this blog). Keep in mind just adding the snatch grip dead lift in consistently was a large increase in deadlift volume compared to what was done earlier in the year. That alone was probably a major contributor to success on the platform. However, the overall volume of the lift over the previous 18 months was at an all-time low. That is undeniable. However, if the right approach is discovered that addresses your specific barriers to progress, you can indeed make progress on a lift with an overall reduction in volume. See the graph I made below that shows my squat and deadlift volume and my deadlift performance (as weight added to my previous 1RM) for reference.

For a little more context there are some other variables in place that are important to note. All probably small, but important aspects that when combined, contributed to the success of this approach. There is a lot of carry over, more than there is for most in my opinion, from my squat to my deadlift. Training my squat 3x per week in a periodized approach, all while making stellar progress over time (it’s easier to do so when the training stress from deadlifting is mostly removed), was no doubt a big contributing factor. Additionally, there is a lot of similarity when comparing MY squat to MY competition (sumo) deadlift:

- My squat has a very “good morning” look to it. My torso is actually more upright on my deadlift than my squat.

- I use a fairly narrow sumo stance on my deadlift, due to limited hip mobility. The difference in my squat stance and my deadlift stance is only about a foot width on each side.

Lastly I stand a LOT. I spend on average 10 to 12 hours on my feet in a standing position every day. This probably has the least amount of effect on the success of this approach, but is worth noting since there is a good amount of strength and endurance that comes from holding good posture for many hours.

Naturally if someone would have told me this approach would work for me I wouldn’t have believed them. In fact I probably would have not followed the program to the letter had it been written out for me. As with most of us meat heads, I would have tried to sneak a quick session in here or a lift there. However, I was literally forced to try this approach due to pain, and lo and behold, I recently hit a lifetime deadlift PR in competition. Hopefully as you read this you will take heart that many times smarter is better than harder.

Leave a Reply