Just like many of you, it was love at first rep for me. I goofed around with weights once or twice in my early teens, but it wasn’t until I got my first gym membership that I really found something in strength training that no sport had ever done for me. To start, I was about as strong as the group of friends I got my gym membership with, but it was obvious right away that I had a certain unique edge when I hit the weights. My friends were more reserved than I, and when it was my turn to hop on the chest press machine, I attacked the weights as if it were something personal. Just when you thought I was done, I found the will to squeeze out an extra rep or two. It would annoy my teenage counter parts, but I paid them no mind. I enjoyed the thrill of fighting the weights, and after a few weeks it was obvious my hard work was paying off, as I progressed much faster than them. The formula was working, so I had no plans of changing my approach.

Per usual, I lingered at the gym a bit longer to read all the “muscle mags” and came across a point-counter-point article on going to failure. The debate was on how often you should go to failure, or if you even need to go to failure at all. In retrospect, it was such a nuanced piece given that this was 1999. To be honest, I didn’t even read the whole article. “What do they know” I thought to myself. Based on my observations there was no other way to train. The gym rats at my gym that went to failure made progress, and the people who lifted half-asleep didn’t. I was 16 years old, and in my mind, there was nothing to discuss here, it was just that simple.

Fast forward three years, and I was at a crossroads of sorts. Progress slowed down tremendously, and I was more open to new suggestions than ever before. I was a regular on every major bodybuilding message board, and this topic came up again. A sample of the guys that were growing quite well were using systems with a moderate amount of sets taken to only technical failure (more on this later) and in some cases, no sets were taken even to technical failure.

After examining the topic closely, I decided it was worth a shot. For a full three months I decided to train this way. It felt odd, and wrong in so many ways. I was not accustomed to leaving the gym knowing I could have done more. I suspect I probably would have bailed out of my commitment had I not seen immediate returns on my investment. Within three weeks I was training with weights I would have assumed were impossible for me. Not only that, but I was able to produce more volume overall despite leaving reps in reserve. I was really baffled as to how training with reps left in reserve was producing more reps than when I greedily got as much out of each set as possible.

Like many bodybuilders, I knew that enduring what others couldn’t or wouldn’t was a huge component of my success. However, I didn’t understand an important principle essential to bodybuilding. In my opinion, a principle just as fundamental to bodybuilding as a high protein diet and a resistance training program. This being the good old Henneman’s Size Principle— which unfortunately most bodybuilders have never heard of. This principle states that you recruit muscle fibers from smallest to largest during voluntary contraction. Typically, from slow twitch (Type I) to fast twitch (Type II) and importantly, fast twitch fibers have the most potential for growth.

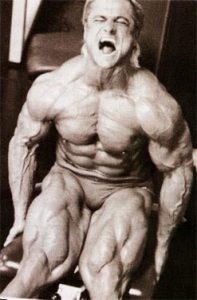

To put it in practical terms when doing a hard set of 10 repetitions we can all generally agree that the first 5 or so reps are pretty easy. At about reps 6 and 7 you have to fight a bit harder to keep the weight moving. The slow twitch muscle fibers can’t produce enough force to do their part any longer, and thus, the fast twitch fibers start to join the party. This distribution of fast twitch to slow twitch muscle fibers grows more disproportionate as you accumulate fatigue during the set, and by rep 8 and 9, despite your best efforts, the load is slowing down a noticeably. Of course, by rep 10 it’s as slow as can be, and you start making those meathead faces we all know and love.

This is a real-world example of the size principle, but if you have never heard of this before, it might change how you view training. One small detail to keep in mind, is that with heavier loads at or above 80-85% you recruit all muscle fibers from the very first rep (keep reading before you commit to only lifting in that loading zone). That rep range will obviously not fit many single joint movements, and the caveat is that designating too much of your volume to these loading zones can wear on your connective tissue. It does bring to light why hitting sets of 2’s and 3’s with your 5RM (5 rep max) on heavy compounds is perfectly viable (in my opinion ideal) option despite what you might see on a bodybuilding cover (you just have to do more sets). Let’s get back on track though…

Now that you understand this principle better, you will be able to understand why bodybuilders who at the very least pace/control how frequently they go failure find themselves making better gains. Let’s examine how this might have played out in my training when I took that leap of faith.

Note: As I brought up earlier, I want to confirm we are on the same page when discussing what my idea of training to failure actually is. I suggest you use technical failure vs absolute failure which requires form deviation, because reps where you deviate from your original form increase your chances of injury. Secondly, in many cases you are displacing the tension from the targeted muscle. Instantly your reps are not just less effective, but potentially more injurious. Therefore, failure in this context is defined by when you can’t perform any additional clean reps.

In this example, all reps that are in bold are assumed to be reps where full muscular activation takes place.

Incline Barbell Press (First Set to Failure/0 RIR*)

RIR: Reps in reserve

Set 1 – 195lbs x 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10 (0 RIR)

Set 2 – 195lbs x 1,2,3,4,5,6,7 (0 RIR)

Set 3 – 195lbs x 1,2,3,4,5,6(0 RIR)

Set 4 – 185lbs x 1,2,3,4,5,6, (0 RIR)

Total number of full activation reps = 9 reps

Incline Barbell Press (First Set 2 RIR)

Set 1 – 195lbs x 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8(2 RIR)

Set 2 – 195lbs x 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8(1 RIR)

Set 3 – 195lbs x 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, (0 RIR)

Set 4 – 195lbs x 1,2,3,4,5,6,7(0 RIR)

Total reps with full activation = 11 reps

In review, the following is what happened.

- By leaving two reps in reserve you had more high value reps compared to leaving no reps in reserve. Volume, when talking about hypertrophy, isn’t just about total reps, but the number of full recruitment reps.

- The load was maintained across all sets and thus, the muscle fibers were exposed to greater amounts of mechanical tension. Mechanical tension being the main driver of hypertrophy.

- With loads left in reserve there is most likely less overall peripheral fatigue taking place, and because of this, a greater likelihood of faster recovery between bouts.

- While this is harder to prove, it’s not a far-fetched idea that when less sets are taken to failure the risk of injury is lower…don’t act like you never been pinned on a squat, tell me that was a safe experience!

In short, this is what happened when I adopted the idea of keeping myself a few reps away from failure. Over the course of many weeks, I saw the benefits and got more out of my training, while controlling the flow of fatigue. Of course, while you can kind of feel this physiological phenomenon (the size principle that is) take place, it was still unclear to me as to what sort of effect this would have on my physique. I mean, I felt less trashed after each session, but that felt oh so wrong. However, better management of fatigue allowed me to increase my loads over the next few weeks as I came into each session fresher and ready to work. Surely, a big part of this was the fact that I was probably running around with more fatigue than my goal required; more fatigue than my body could fully clear on time for my next session to be effective. More so, my progress continued long enough that with some good confidence, I can say that a large part of why this change was effective was due to being able to train in a more recovered state each session. In a nutshell, my training was way more effective and efficient, and it was easier to recover from.

Way too often I see the obnoxious notion that taking the time to learn and being a bit more science/evidence based about your training will tame your beast within. This idea is ridiculous to me because anyone that has lifted long enough knows that being a hard worker is something that is learned over time. Once you become detailed orientated about your efforts, it’s virtually impossible to work under any different “code of effort”. I am not telling you how to train here, but simply giving you a better idea of what is happening under the hood when you do. I know for me, educating myself allowed me to not just work harder (because training is simply more effective now) but it increased my longevity in the sport. I take great pride in my ability to focus and work hard, but had I continued being a weight room cowboy, my tenacity would have been the end of me. In the long term I wouldn’t have come as far as I plan to go. Being a thinking-bodybuilder will never make someone with poor work ethic into an amazing bodybuilder, but it can certainly help a bodybuilder with great work ethic get to a level that would have been inaccessible with work ethic alone. Like many things in life, being rational will help ensure that your efforts are aimed at the right target. In the end, humans are pretty weak animals compared to others, but our ability to rationalize makes us special, and this is something that should be applied to your training if you want to maximize the beast within you.

Amazing post. Learned so much that can be implemented into my own routine. Thanks Alberto

Fucking amazing 😊

I aggree this rir but not the calculation of rep of activation or stimulus reps. If in the first example (failure/0rir) sets 2,3,4 a total of 4 stim sets, no, i believe now reps 4,5,6 are stim reps and on the last set maybe even rep 3. Those sets now make those reps, or require those reps ( failure coming quickly) to recruit more fibers faster. In the end, still its all about mangement of fatigue and periodization.

Just added the reps of stimulus wrong

Exactly my though, if it’s to failure then the 5reps beforehand are effective reps.

Great article! Thanks Alberto