by Josh Pelland BS, CSCS, & Zac Robinson BS, CSCS

2300 words; 8 minute read time

Josh Pelland and Zac Robinson are exercise physiology master’s students at Florida Atlantic University, with Dr. Mike Zourdos, my friend, and colleague at MASS. They coach and make content at Data Driven Strength. I took great interest editing this guest blog, as I’m currently addressing the same topic in peer reviewed and MASS writings, and on our YouTube channel (stay tuned). Hypertrophy progression isn’t straightforward like performance, which this blog clarifies. Thanks Zac and Josh, enjoy!

-Eric Helms, Chief Science Officer, blog editor

Key Takeaways

- Due to the adaptations that occur as we progress through a training cycle, adding sets week to week makes some sense in theory. However, this line of reasoning requires assumptions that may or may not be accurate.

- There are also practical limitations to a proactive increase in sets week to week. Namely, a lack of precision, outside of gym factors, and accumulated fatigue.

- This article also discusses cases in which adding sets is a good idea and when it is not. Overall, it is best to increase sets reactively and when it is suspected that a greater magnitude of training stimulus is necessary for continued growth.

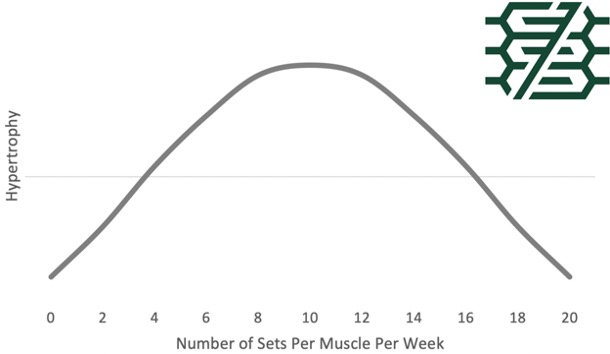

Once intensity (% of 1RM), frequency, and effort (proximity to failure/RIR) are in a good spot, volume drives muscle growth in a dose-response manner. This is true only to a point, and thus this relationship can be conceptualized with an inverse-U curve. Due to this relationship between volume and growth, it is often suggested that volume should be progressed week to week within a training cycle to maximize gains in muscle mass. This article will first explain the theoretical rationale for adding sets week to week. Then, we will discuss the limitations of this strategy and why we generally don’t advocate it. To explain the theoretical rationale, we will use an example. Below is our example athlete’s inverse-U of volume (quantified as number of sets) and muscle growth (hypertrophy).

The number of sets on the x-axis is arbitrary and only serves as an example. Please keep in mind that this figure is an oversimplification as the shape of the curve will vary not only from person to person but even muscle to muscle within the same individual.

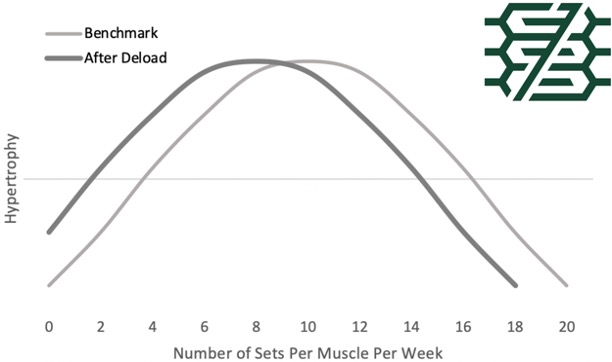

Back to our example. Let’s say the athlete just finished a deload, and they’re entering the first week of a new training cycle. Due to reduced volume and intensity during the deload, they’re slightly detrained and thus theoretically more sensitive to training. To be more sensitive to training means that a more robust response occurs per unit of training stimulus. This concept is illustrated below: our athlete’s inverse-U has shifted slightly to the left due to the deload.

Based on this leftward shift, it makes sense to start the new cycle at a lower number of sets.

After a couple weeks into the new cycle, the athlete has adapted to the new stimulus a bit. In other words, the athlete now sees a slightly smaller response per unit of training stimulus. As a result, their inverse-U is back to the original benchmark. To keep up with the rightward shifting peak of the curve, it makes sense to increase the number of sets.

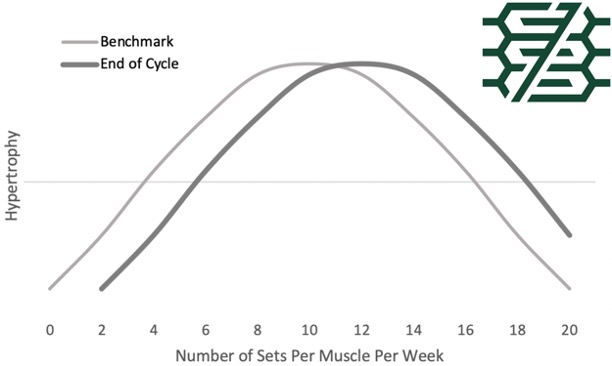

A few weeks later, let’s say week 5 of the cycle, the athlete is well adapted to the stimulus. As a result, they are past their benchmark curve, and it’s now shifted to the right.

Once again, it makes sense to be at a higher number of sets to stay at the peak of the curve.

In summary, as you adapt to the training stimulus, your curve shifts to the right. A greater magnitude of training stimulus is necessary to stay at the peak of the curve and experience maximal growth. An increase in set volume can be applied week to week to keep up with this gradual desensitization that is unavoidable from training consistently.

The example I just laid out wasn’t very granular, but I hope you get the gist of the theoretical case for an increase in sets week to week. Let’s now move on to the limitations of this strategy. The next part of this article will describe why I actually don’t think proactive week to week set increases is the best way to progress throughout a training cycle.

First of all, the need to add sets week to week operates under the premise that the adaptations that shift the curve to the right occur on a short time scale (i.e. week to week). Some might object to this premise. To take this even further, some might object that the curve even shifts to the right at all during an entire training career. Let’s explore that.

Does the curve even shift to the right at all?

Before we explore this question, it’s important to remember that the inverse-U curve quantifies volume using the number of sets performed. So, the need to add weight to the bar or reps to a set at a given load would not represent a shifting of the curve. Let’s think about an athlete that is following a protocol of 3 sets of 10-15 repetitions at 3 repetitions in reserve (RIR). By staying within the RIR constraints of the protocol, the athlete will add load and/or reps at a given load over time. Importantly, this maintains the effectiveness of the sets as the athlete adapts. In other words, adding load and reps maintains the relative stimulus of the 3 sets. This is opposed to the increase in the magnitude of the stimulus that comes from adding sets.

Within the above example, the question of whether the curve shifts to the right is the same as asking whether a fourth set is eventually needed to induce optimal gains in muscle mass. Unfortunately, we’re not sure what the answer to this question is. We simply don’t have data on whether an individual’s set volume requirements change over the course of their training career. This is an important point: just because we have data that suggests greater muscle growth in groups training with higher volumes compared to groups using lower volumes does not provide information about an individual’s inverse-U curve over time.

With all of this said, our hunch is that the curve shifts to the right a bit during a training career and thus increasing the magnitude of stimulus via adding sets is inevitable. However, it’s important to emphasize that the majority of progression over time will be through adding load/reps per set in order to maintain the relative stimulus.

Beyond questioning the premise that the inverse-U curve even shifts at all, there are practical limitations to proactively progressing sets every week. Let’s examine three of these limitations.

1. Lack of precision

In our original example, the peak of the curve was at 8 sets per muscle per week after the deload. Even if you only add 1 set per muscle per week, during a 5 week training cycle, you’ve increased set volume by more than 50%. It’s highly unlikely that the rightward shift in the curve is substantial enough to warrant that dramatic of a change over a relatively short time period. Even if you’re starting with 20 sets per muscle per week, adding 1 set per muscle per week will still result in a substantial change relative to your starting volume.

Since adding one set is a relatively large increase in stimulus, it’s important to remember the earlier point that adding sets is not our only tool for keeping up with the desensitization to training we experience over the course of a training cycle. This brings us back to thinking about load/number of reps per set as our tool for maintaining the relative stimulus of each of the present sets. If you accept that it’s unlikely large enough adaptations occur within a training cycle to warrant large increases in the magnitude of stimulus, it may be best to let natural increases in load/number of reps per set maintain the relative stimulus and avoid being proactive with set additions.

Further, even if significant desensitization has occurred during the training cycle that seems to warrant an increase in the magnitude of stimulus via an increase in sets, it still may be better to hold off. Think about the inverse-U. You’ll make similar progress if you’re slightly undershooting and slightly overshooting the peak of the curve. Thus, for injury risk reduction, I’d prefer to accidentally undershoot the peak and increase set volume when the necessity to do so becomes clear.

To be clear, much of this critique only applies to proactively adding sets every week. Adding a set or two reactively when it becomes clear that an athlete is underdosed and needs a greater magnitude of stimulus for continued growth is a perfectly reasonable way to go. In general, keep in mind the relative change in training stimulus you are inducing.

2. Outside of the gym factors

If you are proactively adding sets each week, you are betting on a reliable rightward shift of the inverse-U curve. What if stress at work or school is high during a week late in your cycle where set volume is planned to be highest? While we should aim to minimize fluctuations in these outside of gym stressors, they are inevitable to an extent.

To be fair, this issue is not unique to a training cycle using a progression in number of sets. However, proactively adding set volume increases the likelihood of falling to the right of the inverse-U peak. If your planned number of sets for the week is 14, and it’s a borderline overshoot of training stimulus, outside of the gym factors can quickly lead to a training cycle falling apart.

It’s important to note that there are other tools like RIR to account for this. For example, even if a week had a pre-planned increase in sets, an excessively stressed athlete will simply perform less reps per set. This is a reasonable way to go, but it’s counterintuitive to reactively reduce the stimulus when you just proactively increased the stimulus. By proactively adding sets, you’re increasing the chance of overshooting training stimulus compared to simply allowing load/reps per set to maintain the relative stimulus.

3. Accumulated fatigue

As you progress through a training cycle, there are two opposing factors influencing your recovery. On one hand, you adapt to the training, and this decreases the fatigue you experience from a given unit of stimulus. On the other hand, this fatigue persists and accumulates throughout the weeks of the cycle. I haven’t mentioned accumulated fatigue until now, but it’s actually working against you as the cycle goes on. Accumulated fatigue works against your ability to perform a given workload. This is the reason deloads are inevitably necessary at some point.

Adaptation to training and accumulated fatigue are opposing forces influencing your ability to perform a given workload. However, the relative adaptation decreases week to week whereas accumulated fatigue adds upon itself each week. With the nature of these competing factors in mind, does it make sense to be at our highest set volume at the end of a cycle when accumulated fatigue is at its highest?

So far, we’ve discussed the theoretical rationale as well as the limitations of progressing sets. Now, let’s consider how the shape of the inverse-U curve influences the utility of progressing sets.

What does the curve even look like?

At the beginning of this article, I mentioned that the provided inverse-U figures were arbitrary. To emphasize that point: we’re not entirely sure of the shape of the inverse-U curve. A legitimate possibility is that the peak of the curve is more of a plateau. This would mean that optimal muscle growth can come from a wider range of volume. If this is the case, there are huge implications for training cycle progression. Specifically, you could move along the left of the curve and still make optimal progress.

This thought experiment is not necessarily what I assume to be the case. Instead, the intent is to think through the implications of the (potentially inaccurate) assumptions we make about the inverse-U curve.

Since we’re on the topic, I might as well throw in the research that sparked this thought in me. A 2020 study from Aube et al. compared quadriceps muscle growth after performing 12, 18, and 24 sets per week. There were no statistically significant differences in muscle growth between groups. In other words, muscle growth was relatively constant in a range of 12-24 sets per muscle per week. These findings suggest a plateaued inverse-U curve. However, the reason I am not pushing this idea is that other research has failed to find a plateau even when using much higher set volumes (such as 2019 studies from Brigatto et al. and Schoenfeld et al.). The point is that we don’t fully understand the nature of the dose-response relationship between volume and hypertrophy and should consider other possibilities beyond the basic inverse-U curve provided at the beginning of this article.

Final thoughts and conclusions

This article is not a comprehensive review of all considerations when selecting a progression scheme. I am also not saying that we should stay at the same set volume to infinity. In fact, there is some evidence that moderately increasing set volume above baseline is a good idea for muscle growth. Due to this line of reasoning, I’m a fan of specialization cycles for muscle growth.

What I am saying is that proactive week to week additions in set volume have important limitations. However, with these limitations in mind, there is a time and a place to add sets each week. In particular, at the beginning of a training cycle, I often conservatively add sets for 1-3 weeks as the athlete experiences the repeated bout effect. Also, Zac, the co-author of this article, has discussed how periods of set volume increases can be helpful in determining where an individual’s “volume sweet spot” is.

It’s also important to note that there may be some utility for overreaching, which is almost always done by increasing set volume aggressively at the end of the cycle. While there is still a lot we have to learn about overreaching, it has potential utility if the following week is going to be a deload anyway. Again, there is a time and a place for set volume increases. However, it should be done strategically and with the mentioned limitations in mind in order to make the best programming decisions for yourself or your athletes.

First of all let me clarify that I don’t use increases in sets as a way of progression, I keep the sets constant with an amount of volume that works for me and then progress through RPE and weight alone, just because I find it easier, but I know people who trains like that.

I think that because the premise of this analysis is not what’s done in practice or what’s normally recommended when this kind of protocol is applied, I have reservations about the conclusions.

As I understood it, the critiques are mainly based on the premise that people start the cycle aiming for the average optimal volume from the beginning, and then the set increases pile up from that number. But in reality, this kind of schemes start with a volume that’s BELOW what’s “optimal” on average, at the minimum amount that gives you some gains, and it’s from that amount of weekly sets that the accumulation starts. In the graphic where 8 sets is the peak on average, if we use a 5 weeks long accumulation cycle, the standard progression scheme DOESN’T call for starting at 8 sets and increasing the amount week to week to 12 as implied, it calls for something like starting at SIX sets and increasing the amount to TEN. The average peak is supposed to be, well, the average of the progression, not the starting point.

If you replace that premise I think the whole critique starts losing a lot of ground, although surely it can still be approached in some new ways.

Hey there, thanks for the comment.

It’s a totally fair point that some may use the peak as the average and not the starting point. However, the aim of the initial example was to simply show the overarching reason one may think they need to proactively add sets each week; that is, the shifting of the curve. However, If I’m understanding your point correctly, I think the rest of the article still applies even if you choose to purposefully undershoot and then overshoot the peak.

Also, if you accept that the relationship between volume and growth is an inverse-U, why would you purposefully undershoot what you believe to be the peak of the curve for the week? I am specifically referring to your idea of starting with 6 sets even if the peak is 8. To be clear, I am putting aside A) deloads and B) any reasons for being conservative with training stress. You alluded to another premise besides the shifting of the inverse-U that warrants a proactive addition of sets week to week, so I may be missing a part of your point to fill in the gaps here.

Either way, I think your example of progressing from 6-10 sets still mostly aligns with A) what we wrote about adding sets for the first 1-3 weeks of the cycle and B) our point that it’s okay to “accidentally” fall to the left of the peak.

Lastly, some of this discussion (both of our points) operates under the premise that we actually know where the peak is. This of course is not the case in practice and is something to keep in mind when actually programming.

In short, I think the critiques of proactive set increases still apply even in your example of progressing from 6 to 10 sets. Let me know if I’m misunderstanding your point and/or if there’s anything here you disagree with! I’m more than happy to discuss this further.

Hey there, thanks for the comment.

It’s a totally fair point that some may use the peak as the average and not the starting point. However, the aim of the initial example was to simply show the overarching reason one may think they need to proactively add sets each week; that is, the shifting of the curve. However, If I’m understanding your point correctly, I think the rest of the article still applies even if you choose to purposefully undershoot and then overshoot the peak.

Also, if you accept that the relationship between volume and growth is an inverse-U, why would you purposefully undershoot what you believe to be the peak of the curve for the week? I am specifically referring to your idea of starting with 6 sets even if the peak is 8. To be clear, I am putting aside A) deloads and B) any reasons for being especially conservative with training stress. You alluded to another premise besides the shifting of the inverse-U that warrants a proactive addition of sets week to week, so I may be missing a part of your point to fill in the gaps here.

Either way, I think your example of progressing from 6-10 sets aligns well with A) what we wrote about adding sets for the first 1-3 weeks of the cycle and B) our point that it’s okay to “accidentally” fall to the left of the peak.

As an aside, some of this discussion (both of our points) operates under the premise that we actually know where our peak is. This of course is not the case in practice.

In short, I think the critiques of proactive set increases still apply even in your example of progressing from 6 to 10 sets. Let me know if I’m misunderstanding your point and/or if there’s anything here you disagree with! I’m more than happy to discuss this further.

This is just brilliant! Wonderful, thought-provoking critique.

It is addressed later in the article, but I would make a case that we may not always be chasing our “sweet spot” so to speak but perhaps are actually looking to try and push the upper end of that curve a little bit more to the right; this, however, does rely on the idea that there is some benefit to doing that — for example, that the ability to train more in an absolute sense correlates with a higher raw magnitude of gains compared to those who train with lower volumes (in an absolute sense) despite both groups of individuals training at their “sweet spots.”

Cheers and thanks for a great Saturday morning read!

I’m glad you enjoyed! Thanks for the feedback.

Your point about pushing the curve to the right is interesting. If pushing the curve to the right (allowing you to perform more volume) did allow for more gains, that would suggest that work capacity is the bottleneck. I expect this only to be the case in A) sedentary folks just starting resistance training and B) when introducing a new exercise, rep range, etc. and before the repeated bout effect has set in.

In general, an increased work capacity simply means we can recover from more sets, not necessarily that we can grow from more sets. Dr. Helms did an excellent job explaining this idea his recent MASS article and the recent Iron Culture podcast.

Very nice article!!

Very clear and exhaustive!

Congratulations for the job done!

Great article, very well thought out and you make some awesome critiques that were very thought provoking. Something that might be worth considering…

Often times proactive approaches to adding sets, load, etc. and reactive/autoregulated approaches to adding sets, load, etc. are viewed as separate and mutually exclusive. I am not entirely sure that is the case. It seems to me, that not only can you proactively plan out set increases for a mesocycle and then autoregulate as necessary (which may or may not need to happen) but that this just might be one’s best option. In this way, one could ensure they are accounting for any potential shifts to the left or right in the curve and doing so in a way that if outside factors become an issue, or the stimulus increase proves itself to be too great, or if accumulated fatigue rises too quickly and too high, the ability to autoregulate and deviate from the plan as needed will ensure that one can respond appropriately in the face of such events. Such an approach may have merit and may potentially be superior to retrospectively adding volume only when the need to do so becomes undeniable.

I’d be curious to know your thoughts on this. Thanks for taking the time to write such a high-quality article!