As my recent contest season ended the reflection began. The scientist in me questioned what was going on at a deeper level as I clung to the direction of my coach (Jeff Alberts) in the final weeks of prep. My trust fell completely in his hands as the calories dropped and the cardio increased. Get Shit Done, was the saying. I couldn’t have dreamed of a better experience. Now – as I’m working my way back to being normal – I can start doing some research.

What exactly happens to the body during a contest prep?

I dug into the literature to take a look. There aren’t many research studies on bodybuilding prep/recovery, but if you want to see the primary data here are some recent publications on natural male bodybuilders:

Natural Bodybuilding Competition Preparation and Recovery: A 12 Month Case Study

A nutrition and conditioning intervention for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: Case Study

Case Study: Natural Bodybuilding contest preparation

And reviews/recommendations:

Dietary Intake of Competitive Bodybuilders

If not, here’s my interpretation

Pre-Competition

The standard process in prep is lose fat and hold onto as much muscle/sanity as you can along the way. This is generally done by decreasing calories and increasing cardio. Historically bodybuilders did this over a period of 8-12 weeks. Yet, there has been a renaissance in natural bodybuilding – the idea that the process is more important than the outcome – which has been led by the 3DMJ team, among others. This idea has helped shape the sanity part of prep. Indeed, if you avoid a drastic 8-12 week cut, and instead focus on a longer prep (14+ weeks) the weight loss doesn’t need to be as extreme, and it may also help retain muscle mass.

Bodybuilders are inherently hard to study. Plus, no two athletes are the same. For this reason, you’ll see most of the recent research is focused around case studies. This makes sense in application too because preps should be personalized to the athlete. Yes, there are some older studies that follow cohorts of bodybuilders through prep, but I think we’ve come a long way since those were published.

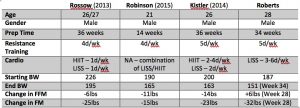

The most comprehensive case study is done by Rossow et al. This study tracked a natural male-bodybuilder (age 26-27) for six months before and after a competition (Rossow 2013). The athlete averaged 4 days of training, working each muscle twice per week – which was recently found to be optimal for hypertrophy (Schoenfeld 2015). The subject also completed 1 day of HIIT (40 minutes) and 1 day of LISS (30 minutes) per week. In addition he practiced posing for 15-30 minutes, 1-4 times per week. I enjoyed this study because I think it’s representative of an average prep.

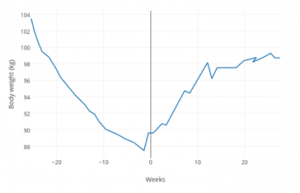

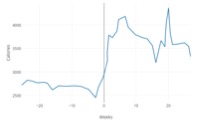

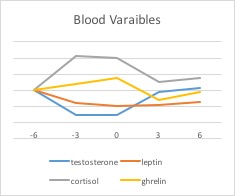

Going into the competition the subject had a decrease in energy intake and body mass, as expected. The subject finished prep at 4.5% body fat, losing ~3kg of fat free mass and 10% body fat from baseline. The novelty of this study is that it measured several hormones. There was a consistent decrease in testosterone, leptin, T3, T4 and insulin during prep. Conversely, cortisol and ghrelin steadily increased as the competition approached.

Weight loss has been known to cause a decrease in testosterone concentration. For example, one study found as few as 2-3 weeks of weight loss can reduce testosterone levels (Karila 2008). Rossow also also reported a decrease in red blood cell count and hematocrit, which was potentially driven by the drop in testosterone.

Ghrelin is a hormone secreted by endocrine cells in the gastrointestinal tract [Kojima 1999]. It has been shown in multiple studies to increase with weight loss [Hansen 2002]. Even if that weight loss is driven by exercise instead of dieting [Foster-Schubert 2005]. Basically, ghrelin is the body’s signal that you need to eat. It drives this process. In one unique study, it was measured in a group of bodybuilders during a prep at 11 weeks out, 5 weeks out, and a few days pre-contest [Maestu 2007]. Much like the Rossow study, ghrelin peaked about ~5 weeks pre-contest. Therefore, as we enter the late stages of prep when hunger becomes a constant issue – blame ghrelin.

Leptin is another hormone that plays a role in energy balance. It is the key signal reflecting adipose stores, and is regulated by adipose tissue [Hovarth 2001]. It fundamentally works as a signal to the body to decrease food intake [Larsson 2011]. In contest prep you would expect it to decrease (it does). This is a double negative in a sense because there is a decrease in the hormone that decreases food intake. Importantly, both Maestu and Rossow found similar decreases in leptin during contest prep.

So, we have two hormones working against us – ghrelin and leptin – both telling us to eat more in a time when we’re trying to eat less. There are a ton of other factors involved in energy regulation, but these are the most well characterized so far. Did I mention how much the body doesn’t like being out of homeostasis?

The Rossow study also found increases in cortisol. Many will interpret this as the body entering muscle catabolism. While that may occur during the end stages of prep, it also signals the increase in fat breakdown. This makes sense because you’re trying to lose fat, the goal of a prep. Another marker of metabolism are T3 and T4. These control thyroid function and appear to mirror the decrease in calories.

A more recent case study was done by Robinson et al., in 2015. This study followed a 21-year-old bodybuilder during a 14-week prep. Much like the previous study, there was a steady drop in calories and body mass. Finally, the last study in the list above was done by Kistler et al., in 2014. Here’s a comparison of the main outcomes from each study:

One thing you’ll notice is the far-right column in the chart citing data from Roberts. I’ve included this unpublished data from my own bodybuilding prep season for comparative purposes. I’m currently tracking post contest measures in hopes to publish the study next year.

Strength

Some physique athletes see a decrease in strength during prep. The Rossow study found a decrease in bench press (-8%) and deadlift (-7%). However, there was no loss of muscle strength in the Robinson study. This could be due to the short duration of prep, but is more likely due to the tests used, since the Robinson study measured isokinetic strength of the hamstrings and quads via dynamometer. These are like the seated leg curl and extension. Unfortunately, the Kristler study did not measure strength outcomes. Again – it makes sense that during a time of caloric restriction, with elevated fatigue, you would see a decrease in strength. It’s just part of the process.

Rate of Loss

When given the choice, most people would choose to suffer quickly rather than slowly. It may be why bodybuilders previously used shorter pre-contest diets. In these three studies there were similar rates of body weight loss. The athlete in the Kistler study lost at ~0.7% body weight per week with 32% of his total loss a result of decreased lean body mass (LBM). While the athlete in the Robinson study dieted at a rate of ~1% BW loss per week and had a higher percentage of LBM loss at 42% of total mass. This suggests that rate of body weight loss may influence rate of lean mass decreases. Indeed, it is recommended that athletes lose 0.5-1% BW (Helms 2014) during a prep. Here’s an interesting quote from Helms et al:

“While greater deficits yield faster weight loss, the percentage of weight loss coming from lean body mass (LBM) tends to increase as the size of the deficit increases [7, 13, 14, 15].… Weekly weight loss rates of 1.4% of bodyweight compared to 0.7% in athletes during caloric restriction lasting four to eleven weeks resulted in reductions of fat mass of 21% in the faster weight loss group and 31% in the slower loss group. In addition, LBM increased on average by 2.1% in the slower loss group while remaining unchanged in the faster loss group [13].”

Psychological Measures

Psychology is a big part of the bodybuilding culture. Most physique athletes want to be considered “hardcore” and love to be in the mindset that they can outwork their competition. This is reflected in a study published in 2012, brought to my attention by Andrea, on the body perceptions and health behaviors of an online bodybuilding community. Think back to the early forum days of bodybuilding.com, where some of the best coaches started. Here’s my favorite paragraph from the study:

“Our results can be encapsulated in the statement that the sovereign rule of the forum declared that muscle trumps everything else. Those who possessed the largest quantity of muscle dominated. Although size was king, muscular performance through feats of strength also commended respect, along with extremely low levels of body fat. As a result, the muscular meritocracy held central its own “holy trinity” in the form of size, strength, and leanness.”

Well, I think it’s safe to say that Facebook has supplanted online forums, but the rise of evidence-based fitness has hopefully altered these patterns.

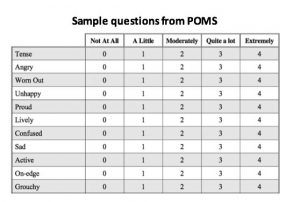

Yet, the direct study of mood in this population is lacking, but in two of these case studies it was measured. The Rossow used a standard POMS questionnaire. This is designed to assess six mood states: tension-anxiety, depression-dejection, anger-hostility, vigor-activity, fatigue-inertia and confusion-bewilderment. A higher score indicates a greater change in mood disturbance. The data showed an improvement in mood until about ~2 months pre-contest. The subject indicated that he enjoyed the preparation and was excited to compete. Yet, four weeks before the competition his mood drastically changed – caused by increases in fatigue and tension, as well and a decrease in vigor. Again, all of this makes sense if you think about it from a prep standpoint. At first you’re excited, maybe you stay excited for a long time. However, once you start digging, things begin to change. You may snap at your family/friends or want to be more isolated to avoid temptation.

This isn’t the case for everyone and, at least anecdotally, it appears to get better with more contest experience.

The Robinson study also measured mood, but slightly different, via the BRUMS assessment, which was adapted from the POMS scale. It has six subsections: anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, tension and vigor. Interestingly, they reported no mood disturbances during prep – even though the rate of bodyweight loss was much faster than the Rossow study. The athlete also reported more stable energy levels, concentration and focus throughout the day compared to baseline.

I think the discrepancy between the mood changes of these two subjects reflects the difference between individual athletes that many coaches see. It just doesn’t seem to affect some people as drastically as others. Personally, it didn’t affect me until about ~3 weeks before my second contest. I started tracking POMS post-contest to determine when I would revert to baseline.

Post-Competition

Returning to normal post-competition is tricky. As soon as you step off stage you probably want to eat everything in sight. Maybe even to the point of sickness. Unfortunately, there’s no data on the immediate post competition period (i.e. hours afterwards), but there is data on several weeks and months post competition. The idea of tracking physiological/psychological measures post competition is very novel, but more data is on the horizon.

The Rossow study shows that during the six months after competition, cardiovascular and blood measurements return to normal. All hormones, except ghrelin and leptin, returned to pre-contest values by 3 moths post competition, likely due to the increase in caloric intake. Strength also seems to return within 6 months post competition. This indicates that most of these physiological changes are driven by the decreases in calories or, partly due to the increase in cardio. From a practical point, all the coaches I’ve spoken to report their athletes are typically back to normal six months after a show. However, some can take up to a year to fully recover. That’s why long a long offseason is important to make progress. If you are continually in and out of prep, the body can’t fully recover. Yes, there are some situations where this can be done but having a long offseason is very important for novice competitors.

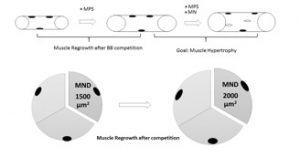

Of note, one of the things anecdotally reported by athletes is a mini-resurgence in strength and muscle size. How can this happen? Well, I recently reviewed it in a book chapter, here’s the take home:

As we decrease body weight, we lose muscle mass. It’s inevitable. However, since it’s not a disease situation (i.e. cancer, sepsis) we still retain the nuclei in the muscle, only the domain shrinks. Yet, when we start increasing food and training volume post-competition, we can quickly increase muscle size/strength. This is known as “muscle memory” by most people. Technically, you can regrow lost muscle much faster than you can further hypertrophy because the foundation is already there. This does depend on the individual, as some will respond much better than others.

As we decrease body weight, we lose muscle mass. It’s inevitable. However, since it’s not a disease situation (i.e. cancer, sepsis) we still retain the nuclei in the muscle, only the domain shrinks. Yet, when we start increasing food and training volume post-competition, we can quickly increase muscle size/strength. This is known as “muscle memory” by most people. Technically, you can regrow lost muscle much faster than you can further hypertrophy because the foundation is already there. This does depend on the individual, as some will respond much better than others.

How do these studies compare to current recommendations and what are we missing?

Well, I think it’s safe to say some odd techniques are slowly being replaced by more evidence-based methods. The days of severe dehydration, crash preps, and odd food choices (remember tilapia skin?) are on the decline. In fact, a scientific recommendation was written by a few leaders in the natural BB field (see above).

Something I want to stress as a scientist is that it’s really hard to study bodybuilders. Furthermore, there’s much less known about women than men, at all physique levels. Luckily, some people are starting to look into the differences. Indeed, this new publication by Halliday et al., sheds further light on the subject. The other issue is that there just aren’t that many bodybuilders out there. Plus, it’s even more difficult when you incorporate the natural bodybuilding controversy.

I’ll end with this – science isn’t everything. A good coach will help you much more than any scientific study. The one thing I’ve realized during my prep is that even the best bodybuilders need a coach to help them through the process. Whether that’s to talk them down from a binge, or keep them from changing something that doesn’t need to be changed. Everyone can benefit from a little guidance.

Well written, well explained. Good use of examples, other case studies, your own experience etc. Good use of practical and statistical meanings behind the data and real word application. Be happy to share my own data which I also just had put in an article with Alan Aragon with data points, pre and post show from my own case study.

Thank you for this clear-cut explanation of the psychology of bodybuilding. This is a very informative and educational article.

It is always my dream to be a bodybuilder…reading your blog.. really inspire me… Thank you!

Great article. I enjoyed all the informative information I read here. Continue writing great articles.